Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming Africa’s economy and society, with potential contributions of $1.5 trillion to GDP by 2030. However, ethical challenges like data sovereignty, algorithmic bias, and digital inequality must be addressed to ensure AI benefits everyone. Africa’s approach blends global frameworks, like UNESCO‘s AI ethics guidelines, with local values such as Ubuntu, emphasizing community and interconnectedness.

Key points:

- AI can drive growth in sectors like healthcare, agriculture, and finance, but risks like unequal access and biased systems remain critical.

- Regional strategies, including the African Union‘s AI roadmap and the Africa Declaration on AI, focus on localized governance and equitable development.

- Countries like South Africa, Kenya, and Ghana are creating national AI policies, but challenges like limited infrastructure, skills gaps, and inconsistent enforcement persist.

- Tools like UNESCO’s Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM) and regulatory sandboxes help startups and governments build ethical AI systems.

Africa’s focus on ethical AI governance could shape a future where technology supports economic growth while respecting local values and human rights.

The Evolving AI Governance Landscape in Africa: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Global and Regional Governance Frameworks

Africa’s approach to managing artificial intelligence (AI) blends global standards with practices tailored to the continent’s specific needs. This dual focus ensures that AI development remains both ethical and aligned with Africa’s unique social and cultural context while addressing local challenges and adhering to international guidelines.

UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence

UNESCO has established the first global standard on AI ethics, which has been adopted by all 194 member states. This framework equips African nations with practical tools to create strong AI governance systems.

One key tool is the Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM), designed to quickly evaluate institutional preparedness. In collaboration with the African Union (AU), UNESCO also developed the Continental AI Strategy. Lydia Gachungi has played a pivotal role in coordinating UNESCO’s efforts with the AU AI Working Group. The framework includes 11 Policy Action Areas, which translate ethical principles into actionable strategies for areas like data governance, education, and healthcare. It places a strong emphasis on diversity and inclusion, safeguarding Africa’s linguistic and cultural heritage. Gabriela Ramos, UNESCO’s Assistant Director-General for Social and Human Sciences, highlighted the urgency of this work:

Governments around the world have decisively moved on from the question of whether to regulate AI to the urgent question of how.

UNESCO’s framework also promotes multi-stakeholder governance, ensuring that international laws and national sovereignty are respected in the use of data. This directly counters concerns about digital colonialism. Building on UNESCO’s efforts, the African Union has crafted its own strategy, further adapting governance structures to Africa’s specific needs.

African Union Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy

In July 2024, during its 45th Ordinary Session in Accra, Ghana, the African Union Executive Council formally endorsed the Continental AI Strategy. Developed over the course of a few months in 2024, this strategy reflects a unified vision for AI across the continent.

The strategy focuses on five key areas: maximizing AI’s benefits, strengthening capabilities, mitigating risks, encouraging investment, and fostering both regional and global collaboration. It targets critical sectors like agriculture, healthcare, education, and climate change adaptation. A detailed five-year roadmap (2025–2030) outlines 15 policy recommendations addressing issues such as intellectual property, data protection, cybersecurity, consumer rights, and competition law.

To encourage thoughtful regulation, the strategy suggests using regulatory sandboxes – controlled environments for testing new technologies – to better understand their implications before full-scale implementation. As the SMART Africa Alliance noted:

Uninformed approaches to governance can lead to systemic biases and overregulation that can and will stifle innovation… At the same time, under-regulation will result in cultivating a culture whereby trust and confidence is absent.

With approximately 2,400 organizations driving AI innovation across Africa, this framework provides essential coordination. In October 2024, South Africa’s Department of Communications and Digital Technologies launched its National AI Policy Framework after completing UNESCO’s readiness assessment. This positioned South Africa as the top-performing African nation in AI, ranking 42nd globally. These efforts culminated in the Africa Declaration on Artificial Intelligence, embedding these regulatory advances into a vision tailored specifically for Africa.

Africa Declaration on Artificial Intelligence

Expanding on the Continental AI Strategy, African leaders have committed to ethical AI practices through the Africa Declaration on Artificial Intelligence. Unveiled at the 2025 Global AI Summit on Africa (GAISA) in Kigali, the Declaration brought together leaders from Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, and other nations to solidify Africa’s AI vision.

This Declaration shifts the focus from global ethical principles to Africa-focused implementation. While international frameworks emphasize universal human rights and transparency, Africa’s approach prioritizes data sovereignty, building local computing capacity, and ensuring AI systems reflect the continent’s languages, cultures, and geographical diversity. Dr. Amani Abou-Zeid, African Union Commissioner for Infrastructure and Energy, underscored this point:

AI systems should be able to reflect our diversity, languages, culture, history, and geographical contexts.

The Declaration also highlights AI’s potential to drive economic and social progress. By creating 500,000 jobs annually and supporting Africa’s growing workforce, AI could inject $2.9 trillion into the continent’s economy by 2030 and lift 11 million people out of poverty. With over 1,000 languages spoken across Africa, developing localized generative AI models becomes a critical priority.

Aligned with Agenda 2063 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the Declaration emphasizes AI’s role in key sectors like agriculture, healthcare, and infrastructure. The focus remains on using AI as a tool for development rather than simply meeting regulatory requirements.

National AI Strategies and Regulatory Frameworks

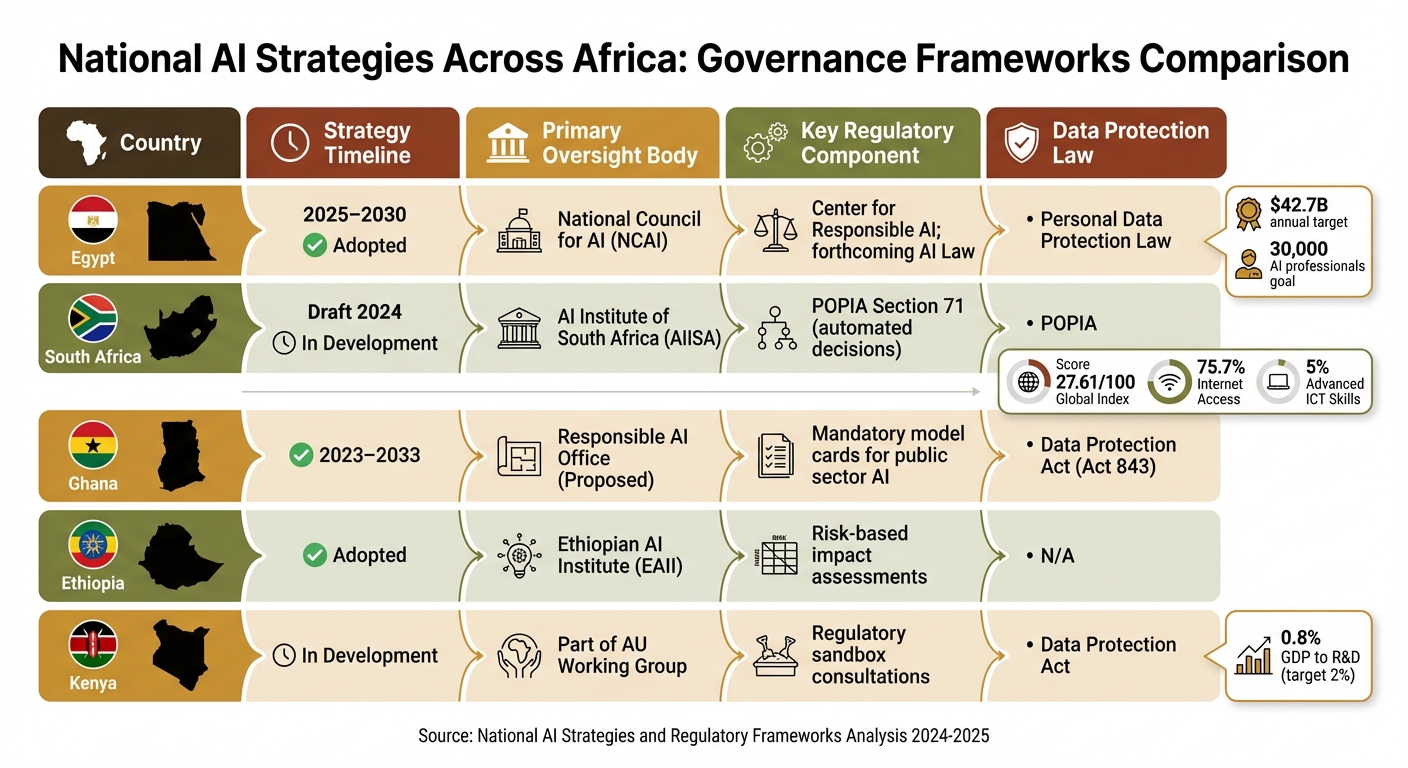

National AI Strategies Across Africa: Comparison of Governance Frameworks

While regional frameworks set the stage, individual African nations are tailoring their AI governance approaches to reflect their unique priorities. These national strategies aim to turn ethical AI principles into actionable policies, creating oversight mechanisms and compliance systems that address local needs.

National AI Strategies Across Africa

Countries across Africa are progressing at different speeds when it comes to AI governance. Here’s a snapshot of some national efforts:

- Egypt unveiled its second National AI Strategy in January 2025, targeting the years 2025–2030. The plan aims to generate $42.7 billion annually and expand the AI workforce to 30,000 professionals. The strategy also established the National Council for Artificial Intelligence (NCAI) to oversee AI initiatives and includes plans for a Center for Responsible AI and a dedicated AI law.

- South Africa topped the continent on the 2024 Global Index on Responsible AI with a score of 27.61/100. The country relies on its Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) to regulate AI, particularly through Section 71, which addresses automated decision-making. A draft National AI Policy Framework was introduced in August 2024, and the AI Institute of South Africa (AIISA) was established to guide implementation. However, challenges persist: while 75.7% of the population has internet access, only 5% possess advanced ICT skills.

- Ghana adopted a National AI Strategy for 2023–2033, proposing the creation of a Responsible AI (RAI) Office to oversee its execution. The strategy mandates transparency in public sector AI systems by requiring documentation like "model cards" and audit logs.

- Ethiopia has formed the Ethiopian Artificial Intelligence Institute (EAII) and focuses on conducting risk-based assessments for high-risk AI applications that could impact life, health, or fundamental rights.

| Country | Strategy Timeline | Primary Oversight Body | Key Regulatory Component | Data Protection Law |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | 2025–2030 | National Council for AI (NCAI) | Center for Responsible AI; forthcoming AI Law | Personal Data Protection Law |

| South Africa | Draft 2024 | AI Institute of South Africa (AIISA) | POPIA Section 71 (automated decisions) | POPIA |

| Ghana | 2023–2033 | Responsible AI Office (Proposed) | Mandatory model cards for public sector AI | Data Protection Act (Act 843) |

| Ethiopia | Adopted | Ethiopian AI Institute (EAII) | Risk-based impact assessments | N/A |

| Kenya | In Development | Part of AU Working Group | Regulatory sandbox consultations | Data Protection Act |

Regulatory Gaps and Solutions

Despite these strides, several challenges hinder progress at the national level. Inconsistent enforcement of data protection laws is a recurring issue, even in countries with well-drafted frameworks. Limited funding for research and development further constrains oversight capabilities and stifles innovation. For instance, Kenya allocates just 0.8% of its GDP to R&D, falling short of its legally mandated 2%. Additionally, the lack of high-performance computing (HPC) infrastructure hampers local AI development and testing.

To overcome these challenges, many African nations are turning to regulatory sandboxes – controlled environments where AI systems can be tested under regulatory supervision without immediate legal penalties. Countries like Mauritius, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, and Kenya have already implemented or are exploring this approach. As the SMART Africa Alliance emphasizes:

"Uninformed approaches to governance can lead to systemic biases and overregulation that can and will stifle innovation… At the same time, under-regulation will result in cultivating a culture whereby trust and confidence is absent".

To further support AI development, the African Union High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) has proposed an African Union AI Fund with a five-year budget of $100 million aimed at fostering startups and advancing research. Countries are also updating laws across multiple sectors – such as intellectual property, cybersecurity, consumer protection, and labor rights – to address AI-related risks without waiting for comprehensive AI-specific legislation. The Malabo Convention, which became effective in June 2023, sets a regional standard for data protection, requiring all 55 African Union member states to adopt it domestically. This creates a shared framework to guide AI regulation.

sbb-itb-dd089af

Tools and Strategies for Ethical AI Compliance

African startups have access to several tools and approaches to help them navigate ethical AI compliance. These resources can assist in implementing the governance frameworks discussed earlier, offering insights that range from national-level assessments to product-specific evaluations.

Using Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM)

UNESCO’s Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM) is a national-level framework designed to evaluate a country’s preparedness for ethical AI implementation. It helps startups identify gaps and opportunities in their local environments by examining five key areas: legal and policy frameworks, social and cultural factors, scientific and educational capacity, economic readiness, and technical infrastructure.

In 2025, Botswana’s Ministry of Communication and Innovation and Malawi’s Ministry of Education, Science and Technology collaborated with UNESCO to pilot RAM exercises. These efforts involved high-level consultations to assess national readiness across the five dimensions, resulting in customized reports aimed at guiding inclusive AI adoption. As Abdul Rahman Lamin, Head of Social and Human Sciences at UNESCO Regional Office for Southern Africa, noted:

This isn’t just about tech readiness. It’s about ethical readiness. It’s about shaping AI systems that respect dignity, reflect our values, and serve all citizens – especially the most vulnerable.

For startups, participating in RAM consultations presents an opportunity to influence AI-related policy development.

The Ethical Impact Assessment (EIA), on the other hand, focuses on evaluating individual AI systems throughout their lifecycle. While RAM takes a broad, national perspective, EIA zooms in on specific algorithms, assessing factors like data representativeness, team diversity, and algorithmic transparency. Conducting ex-ante evaluations – before launching products – helps startups identify potential risks and ensure accountability. Additionally, the AI Governance for Africa Toolkit, created by ALT Advisory, offers practical guidance tailored to the African context, covering governance principles and advocacy strategies.

These tools lay the groundwork for collaborative efforts that refine ethical AI practices.

Collaborative Compliance Approaches

Beyond assessment tools, public-private partnerships and collaborative networks offer valuable resources, best practices, and collective problem-solving opportunities. UNESCO’s Business Council for Ethics of AI unites private sector companies to promote ethical AI development across industries. Meanwhile, the Women4Ethical AI Platform focuses on achieving gender equality in AI design and implementation, supporting both governments and businesses.

One standout example is the South African startup Lelapa AI, which addresses ethical concerns by developing tools for indigenous language processing. This ensures that AI systems are accessible to non-English speakers across Africa, reflecting local social and cultural nuances.

Startups can also benefit from UNESCO’s Global AI Ethics and Governance Observatory, which provides open-source toolkits and documented best practices for responsible innovation. By joining collaborative networks, African startups can tap into global expertise, share challenges, and align with international standards – without shouldering the entire financial burden of compliance.

| Tool/Framework | Application Level | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| UNESCO RAM | National | Assesses country-wide readiness and identifies regulatory gaps |

| UNESCO EIA | Product | Evaluates risks and benefits of individual AI systems |

| ALT Advisory Toolkit | Regional (Africa) | Offers guidance on governance and advocacy for startups and civil society |

| Business Council for Ethics of AI | Organizational | Encourages public-private collaboration on ethical AI standards |

Case Studies: AI Governance Models in Africa

Building on regional frameworks, these case studies showcase practical governance models in Africa.

Kenya’s AI Ethics Programs

In March 2025, Kenya introduced its National AI Strategy (2025–2030), a roadmap for responsible AI development across six areas: infrastructure, data R&D, talent, governance, investment, and ethics, equity, and inclusion [31,32]. This strategy tackles governance challenges in ethics, data privacy, and safe AI deployment, as highlighted by Ariana Issaias, Partner at Bowmans:

the absence of a specific AI regulatory framework creates governance challenges in areas such as ethics, data privacy and safe AI deployment.

A key focus of Kenya’s strategy is data sovereignty – keeping local data under national control – and aligning with the Bottom-up Economic Transformation Agenda to support public services and MSMEs [32,34,31]. Richard Odongo, Senior Associate at Bowmans, elaborated:

The strategy aims to address gaps in AI regulation, investment and skills while fostering innovation in key sectors.

A Technical Working Group, comprising government, industry, academia, and civil society, oversees policy development. Meanwhile, the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) has released a Draft AI Code of Practice and media rules to promote transparency [31,24,32]. The Media Council of Kenya also introduced a Data Governance Guide for Media Practice in 2024 to ensure accountability in AI-driven journalism.

Kenya is adopting a risk-based regulatory model inspired by the EU AI Act. This model classifies AI systems based on their potential risks to privacy and safety, imposing stricter rules on high-risk categories. This approach gives startups time to develop compliance frameworks as regulations evolve. However, challenges persist: Kenya ranks 6th in Africa on the 2023 Oxford Insights AI Readiness Index, but only 0.8% of its GDP is invested in R&D (despite a legal obligation of 2%). Additionally, a significant digital divide exists, with only 17% of the rural population connected to the internet compared to 44% in urban areas.

While Kenya emphasizes a risk-based framework and local data control, South Africa offers a different approach rooted in constitutional rights and sector-specific oversight.

South Africa’s AI Governance Approach

South Africa’s National AI Policy Framework (introduced in August 2024) is built on nine pillars that emphasize ethical design, transparency, and human oversight. The framework leverages the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) to regulate automated decision-making [8,35]. Supported by organizations like AIISA, PC4IR, and an AI Action Taskforce, South Africa leads the continent with strong policy and legal enforcement [8,10]. As the 2025 G20 President, South Africa has also prioritized AI on the global governance agenda. The country ranks highest in Africa on the 2024 Global Index on Responsible AI, scoring 27.61 out of 100 and placing 42nd globally.

South Africa’s governance approach aligns with global standards while emphasizing constitutional protections. The Constitutional Court of South Africa has underscored:

the right to privacy accordingly recognises that we all have a right to a sphere of private intimacy and autonomy without interference from the outside community.

This legal foundation strengthens the country’s AI governance efforts.

The startup Lelapa AI exemplifies South Africa’s commitment to inclusive AI by creating tools for indigenous language processing, making AI systems accessible to non-English speakers across Africa. However, challenges remain: only 5% of the population has advanced ICT skills, and government funding accounts for 56.3% of all R&D spending. Additionally, a 2021 class action lawsuit against Uber is being closely watched as a test case for how courts handle algorithmic management and employment issues.

These two examples highlight how tailored regulatory approaches can address governance gaps and support socio-economic development. Below is a comparison of Kenya’s and South Africa’s strategies:

| Feature | Kenya | South Africa |

|---|---|---|

| Primary AI Strategy | National AI Strategy 2025–2030 (Launched March 2025) | National AI Policy Framework (August 2024) |

| Key Data Law | Data Protection Act | Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA, 2013) |

| Expert Body | Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) / MICT | AI Institute of South Africa (AIISA) |

| Regulatory Approach | Risk-based classification modeled on EU AI Act | Constitutional rights with sector-specific pillars |

| AI Readiness Rank | 6th in Africa (2023 Oxford Insights AI Readiness Index) | Highest in Africa (2024 Global Index on Responsible AI) |

Conclusion

Africa’s journey in shaping AI governance requires a careful balance between encouraging innovation and ensuring protection. The SMART Africa Alliance emphasizes:

Uninformed approaches to governance can lead to systemic biases and overregulation that can and will stifle innovation… At the same time, under-regulation will result in cultivating a culture whereby trust and confidence is absent.

To navigate this, policymakers need to establish clear and actionable regulatory frameworks. These national strategies should align with the African Union’s broader priorities, including the AU Agenda 2063. A hybrid approach – combining strict legal measures with adaptable guidelines and controlled testing – can provide the necessary flexibility for sustainable growth. The proposed $100 million AU AI Fund, which plans to allocate 70% of its resources to early-stage startups over five years, highlights a strong commitment to fostering innovation.

Tech startups across Africa can benefit from tools like UNESCO’s RAM and Ethical Impact Assessment, integrate human-in-the-loop systems as outlined by the Malabo Convention, and utilize regulatory sandboxes in specific markets. However, these efforts must go hand-in-hand with investments in infrastructure and skill development to create a solid foundation for AI adoption.

South Africa and Kenya provide examples of progress with their strategic frameworks. South Africa’s National AI Policy Framework, set for October 2024, and Kenya’s National AI Strategy, expected in March 2025, reflect a growing maturity in AI governance. Yet, challenges remain. Bridging infrastructure gaps, addressing the urban-rural digital divide, and improving skills are crucial. For instance, only 15% of South Africans have basic ICT skills, and a mere 5% possess advanced capabilities. Investing in local talent and infrastructure is not just necessary – it’s critical to ensure AI is developed and applied ethically, driving socio-economic transformation across the continent.

Ethical governance will ultimately determine AI’s ability to positively shape Africa’s future.

FAQs

What are the biggest ethical challenges in developing AI in Africa?

AI development in Africa grapples with several ethical hurdles, including bias and discrimination, data privacy issues, fragmented governance, and the potential to widen socio-economic gaps.

AI systems often mirror the biases present in their training data, which can unintentionally reinforce discrimination against underrepresented groups. For example, if the data used to train an AI system lacks diversity, the results may skew unfairly, marginalizing certain communities even further. On top of this, data privacy laws, such as South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), are still evolving, leaving individuals with limited control over how their personal information is used or shared.

Governance presents another challenge. Across the continent, there’s a patchwork of national laws and emerging frameworks, but their uneven implementation creates inconsistencies and gaps in oversight. This fragmented approach makes it harder to establish unified standards for AI development and use.

Transparency and accountability are also critical concerns. Many AI systems operate as "black boxes", meaning their decision-making processes lack clarity. Without clear audit trails or explainable mechanisms, it becomes difficult to evaluate whether these systems are fair or to address any harm they may cause. If policies fail to include diverse voices, AI risks amplifying economic inequalities, benefitting well-funded groups while leaving women, youth, and low-income communities behind.

Addressing these challenges is essential to building AI systems that are fair, inclusive, and trusted across Africa.

How is Africa’s approach to AI governance unique compared to global standards?

Africa’s strategy for AI governance prioritizes development-focused goals, with a strong emphasis on ethics, human dignity, and socio-economic progress. Instead of following global frameworks that often concentrate on risk categorization or market regulations, Africa aligns AI with broader objectives, such as Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals. This approach ensures AI contributes to inclusive development, advances gender equity, and safeguards cultural heritage.

The continent’s governance approach also weaves AI into existing legal systems, like South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), which addresses accountability in automated decision-making processes. Moreover, regional efforts emphasize building local expertise and involving community stakeholders, tailoring AI policies to Africa’s unique legal and socio-economic landscapes. This stands in contrast to global models that frequently rely on standardized, compliance-driven frameworks, which may overlook local priorities and challenges.

How do national AI strategies help reduce digital inequality in Africa?

National AI strategies are essential for narrowing the digital divide in Africa. They translate broad objectives into specific, actionable plans that cater to each country’s unique circumstances. Key priorities often include improving broadband access, investing in AI education, and reaching underserved communities, such as rural areas and low-income groups. By embedding principles like ethics, inclusion, and diversity, these strategies aim to ensure AI benefits are shared fairly across all segments of society.

Take South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), for instance. This framework safeguards privacy and enforces accountability in AI systems, helping to ensure that the advantages of AI are distributed fairly. Many national strategies also align with the African Union’s vision for inclusive development. This alignment fosters collaboration between governments, civil organizations, and private companies to create AI-driven solutions that address local challenges. Such efforts position AI as a powerful tool for bridging digital gaps rather than widening them.

Related Blog Posts

- AI Startups in Africa: Role of Infrastructure Policies

- How AI Career Tools Address Youth Unemployment

- The Rise of AI Startups in Africa: Tools, Trends & Talent

- AfDB Report: AI Could Add $1 Trillion to Africa’s GDP by 2035